Cerven 10.1942 — Cerven 10.2017 (June 10, 1942 — June 10, 2017)

Cerven 10.1942 — Cerven 10.2017 (June 10, 1942 — June 10, 2017)

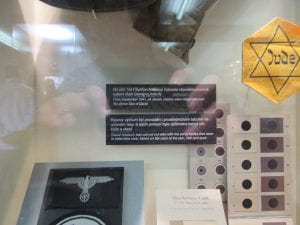

The world’s responses have been swift and persistent, protesting the horrors Adolf Hitler inflicted upon the people of Lidice, Czechoslovakia, on June 10, 1942.

Artists, musicians, poets and horticulturists continue to interpret the significance of the Fuhrer’s vow to erase this Roman Catholic village from maps and memory. Despite Hitler’s pledge, the original village site — 15 miles northwest of Prague — has been preserved, and a new village named Lidice thrives nearby. Bridging the old and new: a public museum and art gallery flanking a vast memorial rose garden. Aerial shot of the rose garden, above, courtesy of Pamatmik Lidice (Lidice Memorial).

Opened on June 19, 1955, the Garden of Peace and Friendship continues to heal the wounds of war. It’s also a popular venue for wedding ceremonies and anniversary celebrations. Its 24,000 rose plants bloom in shades of white, pink, orange and scarlet, signifying “the lost children of Lidice,” the village men and boys murdered by Nazi firing squad, the village women who were sent to Nazi work camps, and the fire that ultimately destroyed the village, including structures dating to the 14th century.

As reports of Hitler’s atrocities rippled across the airwaves in 1942, people throughout the world kept alive Lidice’s memory by naming their babies, hospitals, communities, streets and parks “Lidice.”

The horrors of June 10, 1942, became a wake-up call for Allied Forces in WWII.

Pronunciation of Lidice: leed – yit – seh. Emphasis is on the first syllable.

Copyright 2017 by Elizabeth Cernota Clark

Cerven 10.1942 — Cerven 10.2017 (June 10, 1942 — June 10, 2017)

Cerven 10.1942 — Cerven 10.2017 (June 10, 1942 — June 10, 2017)

The story begins

The story begins